I’m an addict.

The words “psychiatric hospital”, “rehabilitation centre” or even the label “addict” can be, let’s be honest about this, terrifying. The prospect of being ‘put inside’ an institution for an entire month of my life was daunting on numerous levels. I was scared that others would judge me; that my job would disappear and by the prospect of losing sight of who I was. Having spent most of my life avoiding labels like the plague, I wasn’t comfortable slapping this one onto my forehead.

In hindsight, and with the clarity of my newly found sobriety, the feelings of anxiety and fear I had around my decision to choose inpatient treatment were partly justified and partly not.

There is no denying that taking the decision to go to the Nightingale Hospital for 28 days represented an enormous turning point in both my battle with mental health and marked the beginning of a monumental change in my lifestyle. I can now say, with absolute confidence, that taking the plunge and facing up to my problems was the best decision of my life.

What was not justified and what continues to cause unnecessary anxiety and does have to change, urgently and radically, is the stigma associated with mental illness – particularly when it comes to addiction, and how mental health affects men. Society’s attitude towards these issues created inappropriate feelings of anxiety for me and delayed me acknowledging I was unwell and asking for the help I so desperately needed.

Addicts are seen as somehow morally flawed and responsible for creating the bed that they now must lie in. Men are discouraged from showing any weakness. In reality, asking for help is a strength. In our society, it takes real balls to admit you can’t deal with difficult problems and there should be no shame in admitting that you’re struggling and asking for help – this is largely discouraged by the familial and societal systems in which we grow up and in which we are conditioned from a young age.

Before I came to the Nightingale, I’d unknowingly battled for most of my teenage and adult life with patterns of addictive behaviours. I’d developed maladaptive coping strategies and had been using them to run from various traumas that I couldn’t even begin to process – I experienced parental rejection; sexual abuse and psychological abuse during the years that I was meant to be spending developing my identity and discovering who I was. These strategies undoubtedly saved my life. Whilst they were justified reactions, they were not appropriate. They were really harming me on a more fundamental level.

I couldn’t see how hurt and angry I was, and kept putting myself in situations and relationships which caused me to relive these traumas. I had convinced myself that everything was fine, that I was ‘normal’, that these behaviours were in some instances even helpful or had driven me to succeed.

Most unhelpfully, I was convinced that I was in control of my life and that these behaviours were manageable. The truth of the matter was this – I had developed serious substance and process addictions which had rendered my life completely unmanageable. These addictions came to define who I was as a person and meant that I was constantly on the run from my feelings.

There was some truth to my prior arguments that I was in control – I was an extremely highly functioning addict. I had fought my way through the education system after being bullied horrifically at my comprehensive school. My manic drive to escape from my childhood home, where I did not feel safe, accepted or loved, meant I worked hard and ended up with an excellent degree from a world-class university. I had a fascinating and varied early career and I am now on long-term sick leave from a job that I loved and in which I was valued and respected as a highly performing team player and leader. I’d travelled to all corners of the world, meeting incredible people and seeing things many people would never have the chance to see. I hid my issues well, so well in fact, that my brother told the Nightingale’s family addictions therapist that he was sorry but he’d come to the wrong group – his brother was absolutely not an addict, and he’d need to go and find the correct room. How wrong he was.

I clung to all of these achievements and my skill at outwardly showing strength with a panicked sort of pride, but my outlook was fundamentally flawed – my fuel tank was completely empty and my CV, list of relationship conquests and travel scratch map were the most important parts of my identity. I was in denial that anyone really cared about me or valued me and was convinced that everyone was out to get me. All of the achievements were marred, blurred or forgotten but the constant using I was doing in secret and ashamedly around them.

Others would react with excitement about my latest trip or achievement and I would react with ambivalence at best, with complaining about my life more often. I had ticked off most of a fairly comprehensive bucket list by my mid-twenties out of sheer panic but when looking back on the last few years, I felt absolutely no joy or emotion about the incredible opportunities I had snatched. I’d done everything out of fear of having to return to face my issues and hadn’t been emotionally present for pretty much all of it. I was so focused on achieving and succeeding to get validation from others that I had no idea what I wanted to do, and I left a trail of emotional destruction behind me on my warpath.

The reality of the situation was that my behaviour was consistently escalating. My perceived ‘control’ over my addictions was waning. I was putting myself in increasingly dangerous situations, making increasingly bad decisions and felt like I was constantly teetering on the precipice of disaster – which I was.

I’d had a few mini breakdowns in the past, but had always covered them up to myself as stress related and got back on my feet after a couple of days or having made some half-baked effort to attend some form of NHS CBT (all I could afford) a couple of weeks a month for a short period of time.

This was never a real fix, and I got extremely adept at telling therapists what they wanted to hear and then running back off into my coping strategies of choice – whether this was an obsession with sex, video games, cigarettes, weed, hook-up apps, love, narcotics, work or booze – my addiction of choice changed frequently and subtly, making it harder for me and others to notice that I was an addict, or to understand how dangerous addiction is.

A series of unfortunate events following a string of exuberant and unnecessary work trips brought me to my knees earlier this year. I was exhausted. I’d made myself sick through a number of bad decisions. I was unable to stop compulsively going back to see toxic and abusive men who were clearly manipulating me out of their own shame and damage.

The breaking point came when I found out a friend I had previously dated had passed away. I found out when I went to message him on Facebook to ask for advice about my increasing substance abuse, something he’d had to deal with before. I hadn’t noticed that he had died over two years ago as I was so self-obsessed within my addiction, and I was slapped in the face with a profile that now said “Remembering”. I had seen him on a friendly basis weeks before he died, and we’d talked about some of the things he was struggling with. I think, looking at it now, we had got along so well as we had such similar issues.

I set about manically investigating the circumstances of his death, and they seemed suspicious to me. They fit a pattern of behaviour, namely putting oneself in potentially dangerous situations, that I could see in myself.

In exhaustion, I sat in my bedroom and let my life fall apart. I isolated myself, cancelled a work trip saying that I was ill and ignored all my work devices completely for two weeks. I convinced myself nobody would notice. I missed the weddings of two of my closest friends; a conference which I had been invited to on the back of two years of difficult and emotional work. I disappeared without explanation on friends I was meant to be going away for a week with. I sat in my toxic shame and used non-stop.

After a few weeks, a close friend from work tried to reach me again and I finally picked up the phone. We both burst into tears and she convinced me that I needed to get some help and that everyone was extremely worried about me. I will forever be grateful to her for the love and understanding she showed me at my rock bottom. My job and relationships were at risk by this point, too. Another friend found out I was off work and told me about the Lloyds’ CEO Antonio Horta Osório’s struggle with burnout and suggested I read about his journey. I found a few articles and was shocked – I hadn’t realised asking for help and being able to go somewhere where I could shut out the outside world was an option. His story inspired me to ask for help.

In desperation, I reached out to the consultant psychiatrist I had started seeing a few months previously for feelings of depression and anxiety. These were, with the clarity of hindsight, suicidal ideations caused by the un-manageability of my addictions. She made time to see me at the earliest opportunity and I confessed to my substance dependence. I spoke to her about Antonio Horta Osório’s time off work and she concurred – it sounded like inpatient treatment might be a good idea. I was terrified, but the hard part – telling others about my issues – was already done. Once my insurance approval came through, after a testing battle with the insurer and the help of my employer, my overwhelming feeling was relief. I told myself that if I was going to get help I could at least go on a last hurrah manic rehab shopping spree – if I was going to be an inpatient, I would at least be the most fashionable and well prepared inpatient they’d ever seen.

I arrived on a Monday morning (late but fashionable, owing to the previous night being spent using instead of sleeping, as was my norm by this point) flanked by two close friends who I’d asked to make sure I got out of bed and didn’t chicken out at the last minute. I was made to feel reassured by my consultant, the nursing staff and the therapy team and quickly settled in.

Immediately, I was bowled over by group therapy. I had found people who had the same experiences as me, who were being honest about it. It was like a sledgehammer. Empathy started flooding through my body. I felt physically lighter as I started sharing my worries and experiences and working the 12 Step Programme.

After a few days, a few of us noticed that the staff seemed to be talking about us. They seemed to know what I was struggling with without me having to tell them, and would gently tailor my care plan and check in with me throughout the day when I was having a tough time.

At first, I felt paranoia – something I suffered from frequently when I was using. Then it hit me. These people were talking about me, but they were plotting how to support me. How to help me. There was a conspiracy in the hospital, but it was a conspiracy of kindness – a seamless experience of compassion and care tailored just for me.

The conspiracy ran deep and was much more extensive than I had expected. There were the foot soldiers of the hospital Illuminati – the wonderful, kind nurses that went above and beyond to listen to me, to collaborate with me on my care and give me space to express my emotions. Their experience shone through and they guided me through what would otherwise have been an intensively confusing and difficult process.

The magicians of the hospital – the therapy team – are without exception world class. I could feel the hundreds of years of experience they had between them, with many of them inspiring figures in recovery themselves. The team are a fountain of knowledge, motivation and wisdom who are driven by a passion for recovery. They were strict, but absolutely fair, and I was most struck by their honesty and their willingness to receive feedback and humbly join the group in our journey of self discovery, particularly regarding the experiences of LGBTQ+ people and other marginalised groups.

The mastermind of the whole operation – my consultant psychiatrist – has consistently exceeded my highest expectations for care, without the slightest trace of judgement. No question has been too stupid, awkward or too much trouble for her. She oozes with a clear passion not only to understand my feelings and to help me but to see me recover and thrive. She has without question been the keystone of the support network that has saved my life.

I am completely overwhelmed with gratitude to the staff who made me feel so comfortable and who helped get my head screwed back on so successfully. The close working between the different parts of my team was so essential as my suppressed emotions started to flood back. The nurses, therapists and my consultant created a cushion around me that gave me a safe environment to work through things I was previously unable to stare in the face.

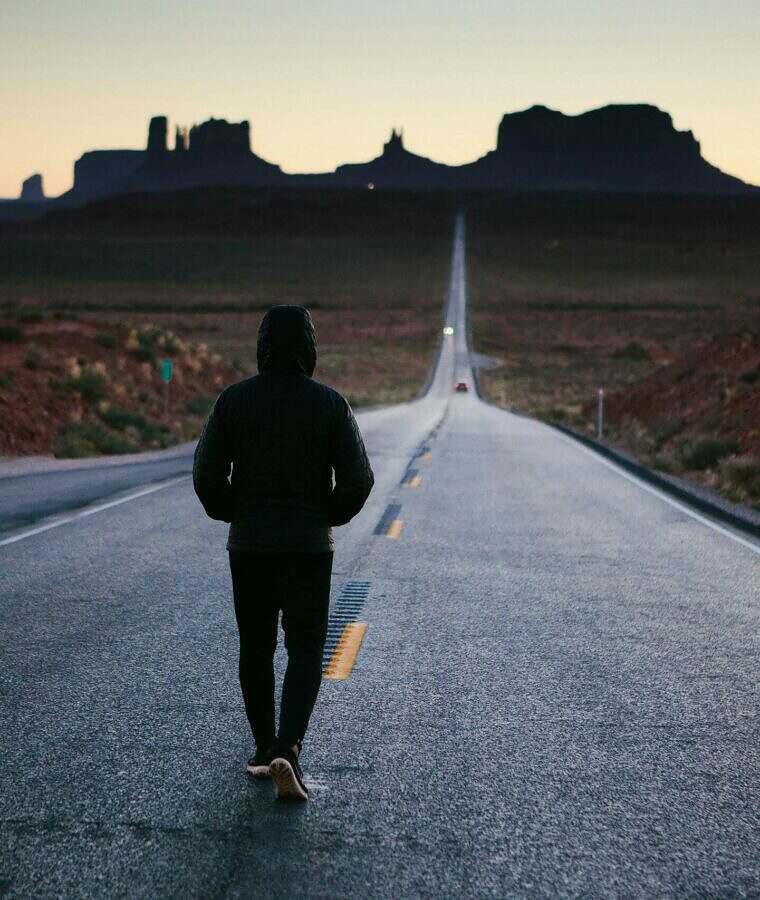

Don’t expect this process to be a magic bullet. I now think of it more like the unveiling of the secret map to a long, winding, and at times steep yet mind-blowingly beautiful hike you never knew existed, but that actually starts just around the corner from your house.

The process is hard work, and it requires focus and perseverance. Hiking boots, equipment and Sherpa will be provided but if you aren’t willing to commit, then don’t waste everyone else’s time. I don’t say this to put you off, but to be frank with you. Don’t waste your money and time if you aren’t open to the help offered; to be honest about where you are and how you got there or if you aren’t willing to commit to the full programme, as uncomfortable as parts of it undoubtedly will be.

This is a recovery programme, not a detox clinic, and you will have to stare directly over the chasm of the consequences of your behaviour and choose life over death.

Addiction is a progressive and fatal illness and the programme, cross-functional team and the other patients (who will be your peers and may well become an invaluable support network in the outside world) all deserve to be treated with the absolute respect that matches the gravity of our condition. Going to the Nightingale is an enormous privilege that many still suffering addicts are not afforded and should not be wasted or treated with contempt.

Nightingale gave me incredible opportunities – firstly, to take time away from me to clear my sight and clear my head, in a safe and structured environment.

I received help to identity the root causes of my maladaptive coping strategies and started to build more healthy and effective ones.

I was showered with opportunities for creative and communal expression, through both innovative and traditional therapeutic and well being programmes, that allowed me to reconnect with my emotions and my body – which I had largely forgotten existed.

Unexpected favourite programmes of mine were the 12 step programme, art therapy, anger and relationship management classes and equine therapy in Richmond Park, led by a wonderful equine psychotherapist and his team of surprisingly effective and beautiful therapy horses.

During my stay at Nightingale, almost everything that could’ve gone wrong for me happened. I had my life savings stolen by an identity fraudster. My relationship with my parents sunk to an all time low. Things shifted at work, meaning that particular dream job was no longer an option on my return to work. If I’d not been clean and surrounded by the team at the Nightingale, I don’t know where I would have ended up. I felt completely naked, all of my armour shattered, but for the first time in my life I was able to begin dealing with these world shattering events like a rational, responsible adult.

If I hadn’t had help, I don’t think I would’ve been able to cope. To be completely honest, it’s not a stretch to say I could be dead right now, whether through a poor decision or simply neglecting myself.

You don’t leave the Nightingale with a big bang – my peers and I now jokingly say that we “transition” into the new life that you start to build there. That’s where the work has really begun. I left the hospital with my head clear. I left the hospital full of hope. Having entered with absolutely no self esteem, I left with a strange sensation of fondness and trust in myself. I left the hospital feeling like I want to live. I had the epiphany that I wanted to live during my stay and it was one of the most emotional realisations of my life, and one that I cannot begin to express gratitude to my entire support network for.

I am now taking time for myself to go on a serene journey of self-discovery and I am working to understand who I really am for the first time in my life. I am learning to be patient and self-compassionate as I go through this process. I am not sure when I will be ready to return to work or to begin the work of repairing relationships and making amends for my past behaviour.

I do know that I feel more stable and equipped to begin unpicking my problems and to deal with life on life’s terms now than I have ever have done in my life, whilst recognising that I am and will likely always be a vulnerable person who needs to ask for help frequently and actively. I continue to receive support from my team at the Nightingale, my recovery peers, and the NA rooms as I maintain my sobriety, make lifestyle changes and seek to begin processing traumatic experiences from my past more fully.

When my favourite nurse, who has been absolutely instrumental in my recovery, asked me if I would be willing to share my story, I baulked. It was a trap, my addict brain told me. I hesitated. I talked to my support team. I went over it again and again in my head. Posters told me that my story was powerful, and I didn’t really allow myself to connect with them because of the feelings of toxic shame about my behaviour and self I am still working on learning to manage.

The most powerful thing I have learned in my recovery is that the opposite of addiction is actually connection. I thought about how much the stories of others had inspired me to give myself another chance on a different path; how much hearing from my peers about their journeys had galvanised my recovery and how the experiences of my fellow recovering addicts are actively helping me to stay clean, and I started writing. Being honest and open still does not come entirely naturally to me, but I hope that if one person finds my experience helpful in the same way I found others’ then sharing my story will indeed have been a powerful and worthwhile experience.

If you feel like you are ready to give up on your way of life, if you feel like you can’t do it anymore and are willing to commit to honesty and hard work – take the plunge. I was surprised at the momentum you quickly gain when actually taking time to make decisions in your own interest.

If you do choose the Nightingale, you’re jumping straight into many pairs of very, very safe hands. Ignore the stigma. You are strong and you are a good person. You just have to ask for help. The help is there.

– Written anonymously by an inpatient