I’m Tana Macpherson-Smith, and I’m a former patient of Nightingale Hospital.

My story of mental health starts from the age of 15 months old. When my mother was sixteen weeks pregnant with me, she was told she had acquired an autoimmune disease and would not only quickly become fully paralysed, but the illness was terminal. She had two small children and me on the way. That news must have been terrifying and devastating for her. By the time I was two, she was a quadriplegic. She was everything to me, despite never being able to hug me or speak to me. She died just before my eighth birthday.

After her death, we were rarely allowed to speak of her. In those days, there was no therapy available for me, nor anyone who thought it was needed. My siblings were sent away to boarding school, which made my mother’s death feel like a triple bereavement. I missed them so much. From then on, I buried my grief during the day and cried behind closed doors at night, always. I was never able to talk about my sadness growing up.

Instead, I wrote about grief, loss, abandonment and loneliness in school essays, earning A++ grades, with teachers praising my outstanding, emotive, detailed writing, yet not one of them ever asked if I was okay.

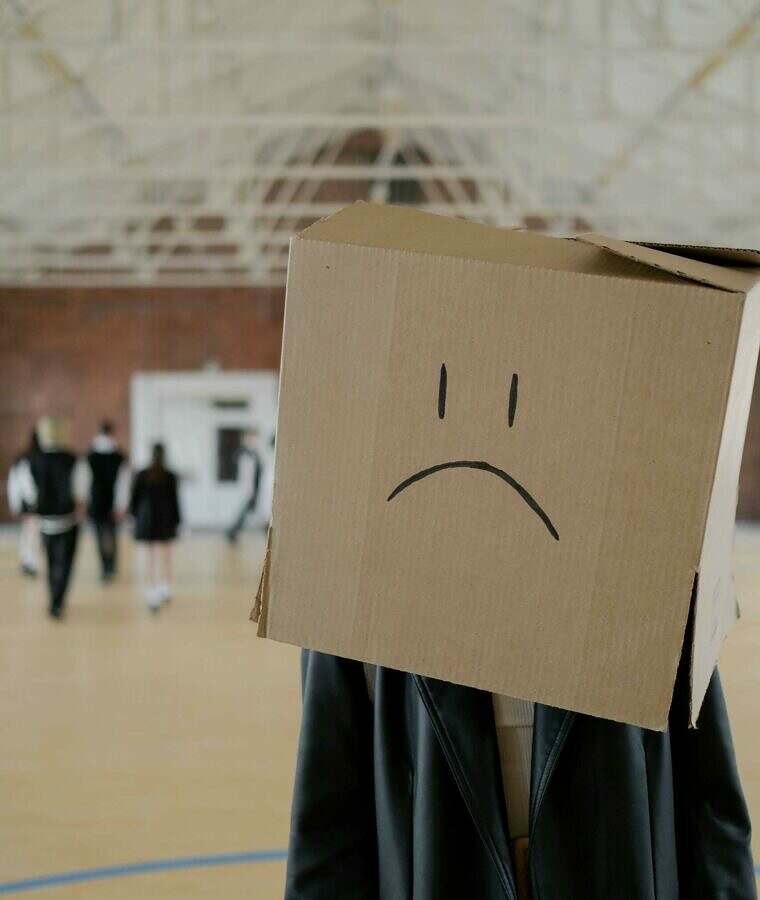

Looking back, I now understand that all of this created a deep limiting belief: that I am invisible.

As an adult, I was being treated for depression. However, I never truly accepted that I had depression or anxiety. I had been on beta blockers quite often, but I assumed that my heart was racing due to often working 110 hours a week. I was literally on call seven days a week. I was on and off beta blockers and other medications, but I never thought much about it.

I was still reeling from the impact of a long-term, incredibly difficult period of bullying and emotional abuse. When the person at the centre of the bullying and control was no longer in my life, I thought everything would improve, but instead, I started to feel overwhelming anger about the impact that period of my life had had on my family and me. I have always maintained “I don’t do anger!” so this was an alarming experience.

Around this same time, I discovered I had a 10-inch tumour in my pelvis which required surgery, including a hysterectomy and further emergency surgery just three weeks later. I returned to work too soon after the surgery. I wasn’t physically strong enough to suppress the emotions I had buried – about the abuse, about my past, about everything. The anger kept building, lifting the lid on emotions I had buried my whole life.

Needing to get away from everything, I sought therapy in Thailand, attending daily sessions for ten days with an incredible English therapist. But when I returned, the anger still grew. I lasted six more months before realising I wasn’t in the right emotional state to work effectively.

One morning, I took an early morning yoga class to ease my emotional state. As I was driving home on a dual carriageway, a passing ambulance suddenly turned on its sirens and flashing lights and raced off to rescue someone. As if someone had pressed a switch, I put my foot on the accelerator, reaching upwards of 85 mph whilst looking for a tree with which to connect.

It was never about wanting to end it all – I have always loved life. But at that time, a voice in my head told me that if I was injured badly enough to be in intensive care, ‘they’ would finally understand the damage they had done. Who ‘they’ are, I can only surmise. The bully? The many people who knew what was going on but chose to turn a blind eye, or was it the predators who sexually harassed me from the age of five?

That day in the car, the last thing I saw was a tree in the middle of my windshield, rushing toward me at high speed. In slow motion, I prepared for the impact, expecting that finally, someone would see me. But when I came to, I realised I hadn’t touched the tree. Somehow, I was 200 meters down the road, the car had spun, and I was physically unharmed but emotionally shattered. Had I hit the tree at that speed, I wouldn’t have been in intensive care; I’d have been in a coffin. All I can believe is that it wasn’t my time to die.

After everything that happened, I saw a doctor, who referred me to Dr Elza Eapen. She suggested I come to Nightingale Hospital, where I spent not the expected three days of assessment, but a full six months. I was an inpatient for about nine weeks before being discharged as a day patient.

However, I was later readmitted due to catatonic dystonia, which happened following an intense therapy session. I went into a state of complete paralysis in a deeply uncomfortable position and was unable to move or ask for help for several hours. I was readmitted to the hospital and spent more time as an inpatient before attending the day programme for another three months.

Surprisingly, I remember every single detail of my time at Nightingale. My commitment to my recovery was so evident – I attended every single session, seven days a week. It was an extraordinary experience, and I am profoundly grateful.

How did you find your treatment? What were the most valuable lessons you learned?

Travelling to the hospital on my first day, I had imagined – and feared – a stereotypical psychiatric ward. What I walked into was completely different. My room was beautiful, with a view toward Marylebone Station. The environment, the carpets, the artwork – it was all so calm. But most importantly, I felt cared for. That was what I needed most, after a lifetime of caring for others.

But my time in hospital wasn’t just about resting and letting people care for me, I also had this overwhelming desire to feel like someone, for possibly the first time, would recognise the pain I was experiencing. I would sit behind doors watching to see if the nurses would look for me, even stand behind curtains, just to know that someone was looking. For the first time ever, I attempted self-harm. Immediately afterwards, I showed the nurses what I had done. I had spent years helping teenagers through similar struggles, and now, here I was, screaming through my actions: “Will somebody please see me?” Looking back at my time in the hospital, I now realise that so much of my behaviour during those six months was about wanting to be seen.

I was constantly reminded to stop worrying about others and focus on myself, which was incredibly difficult. But I committed fully to my treatment. I attended two or three sessions a day. Dr Eapen’s care was beyond extraordinary. For someone who had always felt invisible, suddenly, I was truly seen.

How has your life changed since completing treatment?

Coming out of treatment, I knew I had to change the trajectory of my life. Therapy helped me see my true self and believe in my own capabilities – something that had taken a lifetime. On leaving the hospital, I felt I had no choice but to leave my beloved teaching career, as I needed more time to recover fully.

Over the past eleven years, I’ve spent time deeply analysing my experiences and coming to understand the foundations for my limiting beliefs: that I am invisible, however hard I try I will always fail and that I am not good enough to be believed. Through this process, I have not only learned how to break those patterns but have researched extensively to understand why so many ordinary people, just like me, find themselves experiencing such serious mental health issues.

Since then, I have dedicated my time to training in multiple therapeutic disciplines and becoming a mindset transformation coach. In 2015, I founded ClearMinds Education with the aim of transforming the lives and emotional wellbeing of children and teenagers. I have never been happier than I am doing this work

Now, I’m on a mission to change the face of mental health by putting the focus firmly on prevention from an early age. On top of my work as a coach, I am a mental health advocate, speaker, author and a child and adolescent therapist. My Monkey Wisdom Programme helps those who parent, care for and educate children of all ages to understand the profound impact of our words and behaviours on the mental and emotional wellbeing of children and teenagers and long-term, the impact on the mental health of adults.

My debut novel, There’s a Monkey on Your Shoulder, published in November 2024, was written not only as a high-octane insight into mental health and mindset for teenagers, but also for any adult wanting to better understand their own mental health or that of the children in their lives. I never anticipated that it would prove a winner with people in their seventies and eighties too, who tell me it is making sense of their lives, given that no one was ever talking about mental health when they were growing up.

If you could share something with someone who is in the place you were 11–12 years ago, what would you say to them?

Absolutely do the work. No matter how hard it is, show up for the sessions and fully engage. Explore as much as you can because true healing requires effort. Nothing comes easily, and if you shy away from the process or don’t put in the work, you won’t have a real chance at getting better.

It’s also important to know that recovery is possible. There are many different therapies and approaches available, and while you won’t always have a therapist by your side 24/7, there are powerful techniques for self-regulation that can help you manage your emotions. It’s essential to be honest about how you’re feeling and to let people know what you’re going through.

When you’re in the depths of it, it’s easy to keep turning to the same people for support, but if they’re not equipped to help, it can feel like nothing changes. That’s why being open to seeking the right help is crucial: there is a path to healing for everyone, and the right therapy can make all the difference.

There are so many little nuggets, moments, and so many memories. One that stands out is the first few nights at the hospital when the door would open every 15 minutes, night and day. The door would open, and the light briefly shone in as staff checked to make sure I was safe. It had never occurred to me that this level of care and attention was something I needed, but looking back, it meant everything.

Now, I have a much deeper awareness of how much of my life, and particularly that six-month journey, was about my struggle with invisibility. I no longer feel invisible; I am no longer on any medication. I have a real purpose, and I absolutely love my life.